Peace Actions Envisioned by Our Children:

From Memory to Record, Weaving Our Hopes

Eighty years have passed since the end of the war, and "passing on memory" has become an ever more pressing challenge. To help hand down survivors' testimonies and hopes for peace to the next generation―and to have children themselves take up that role―the City of Hiroshima, a self-declared City of Peace Culture, has run the Children's Peace Summit since 1996.

As part of the program, all sixth graders at municipal elementary schools (and at national and private schools that opt in) write essays on peace. Following screening, two students are chosen to read a Commitment to Peace at the Peace Memorial Ceremony on August 6, delivering their words to the world.

The 2025 representatives were Shun Sasaki and Chieri Sekiguchi. At a ceremony attended by representatives from a record 120 countries and regions, they shared their thoughts. As two students who have rich international-exchange experience, what were their thoughts about carrying on memory and peace. On the eve of the final Children's Peace Summit activities of 2025, we asked them their thoughts.

With Representatives from 120 Countries and Regions Looking On

Hiroshima's Youth Delegates Deliver a "Commitment to Peace"

On August 6, 2025, the anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima by the US army, about 55,000 people gathered for the ceremony in Peace Memorial Park, including hibakusha (survivors of the atomic bomb), bereaved families, and overseas attendees. With international media also carrying the event, Sasaki and Sekiguchi spoke in unison:

"...we will build peace by continuing to convey the will of the hibakusha and weaving our voices together as one."

When the roughly five-minute commitment speech ended, a long, loud round of applause enveloped them. "After the ceremony, we were surrounded by so many people telling us it was amazing, it was wonderful. Someone from Mexico even gave us sweets. I hope our words reached people's hearts," Sekiguchi recalled with a smile.

The Commitment to Peace is part of the Children's Peace Summit (※1), a City of Hiroshima peace-education program centered on "preservation" and "transmission." Sixth graders at municipal schools, as well as national and private schools that wish to participate, submit peace-themed essays that are screened first at their schools and then by the City Board of Education. Twenty students are selected to present their ideas at a public session in June, and the two recipients of the Peace Summit Grand Prize are chosen to read that year's commitment speech at the ceremony―effectively serving as representatives of Hiroshima's elementary school students. As Sasaki put it, "I'd wanted to read it since third grade," and many children look up to the role. In 2025, the thirty-first year of the program, 10,465 essays were submitted from 144 schools.

The commitment speech, however, is not written by the two readers alone. All twenty students from the presentation session discuss and draft it together at a Commitment to Peace review meeting. A Board of Education staff member who facilitated the discussion noted, "We felt a strong awareness among the children that they would be the ones to carry memory forward and to speak out." As of the end of March 2025, the average age of hibakusha had surpassed 86, and the number of registered survivors stood at 99,130, falling below 100,000 for the first time. Among the children, there was a shared sense that "we may be the last generation able to hear their stories firsthand."

We Wanted to Convey the Power We Hold

To Change a World Still at War

Another point the children were determined to emphasize was the message that they, too, can act.

"One voice. When spoken with conviction about the facts they learned, even just one voice can make a difference."

It was Sasaki, who has studied English since he was seven months old, who read these words aloud. He has been giving individual tours in Peace Memorial Park for overseas visitors since second grade.

"What made me happiest was when someone I guided told me, 'I used to think the atomic bomb ended the war for the better, but after hearing you, I thought we should get rid of nuclear weapons.' It made me realize I do have the power to change something. We wanted to say that we, too, can be the one voice that changes the world."

In the Commitment to Peace, they spoke not only about the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima but also about wars currently taking place around the world. "The atomic bomb was eighty years ago, but war is still happening. It's not something far away," Sekiguchi said.

Since Russia's invasion of Ukraine began in February 2022, she has spent time with Ukrainian mothers and children who fled to Japan. As she formed a friendship with two sisters who came, leaving their father behind, she grew to realize firsthand that war robs people even of the everyday life of living together as a family.

Recognizing Differences as a Good Thing,

Weaving Peace by Valuing Every Single Voice

What should we do? Both students emphasized the importance of dialogue. They said that talking with people from different backgrounds brings countless discoveries.

In the final line of the Commitment to Peace introduced at the beginning of this article, the expression used is "weaving our voices together as one." At the ideas meeting where the twenty children gathered, they discussed why it should be "weave" rather than "connect."

Sekiguchi explains, "'Connect' gives the image of lining up individual voices into a single chain, but 'weave' suggests carefully layering each voice without forcing them into one. 'Weave' felt closer to what we meant."

Asked how it felt to send their message out to the world, Sasaki said, "You can't put a score on it. What matters is how the people who heard it will act." From outreach to dialogue, and then to action―this is the form of transmission they envision.

The Children's Peace Summit continues beyond August 6. At the Honkawa Elementary School Peace Museum (※2)―located just 410 meters from the hypocenter and preserving parts of the school building that still bear the scars of the bomb―the children who took part in the presentation meeting served as volunteer guides.

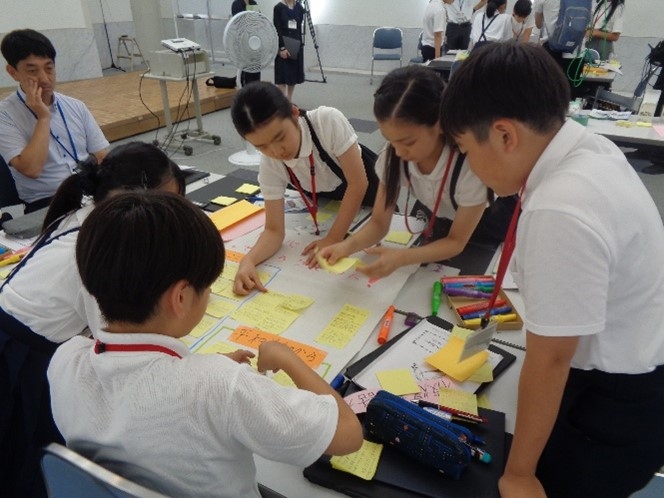

Serving as a volunteer guide at the Honkawa Elementary School Peace Museum is the culmination of the Children's Peace Summit. It is a place for participants to digest what they have learned and thought about peace and to convey it in their own words. On the day, nine of the twenty participating children took part, split into three groups to guide visitors. In preparing, the children themselves led weeks of discussion about what they wanted to communicate, and they continued rehearsing right up until opening time.

"Did you know the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima did not hit the ground, but exploded 600 meters above it?"

"How many people do you think survived here at Honkawa Elementary School?"

"This column on display was taken from part of the Atomic Bomb Dome. Please touch it―doesn't it feel rough?"

What all the groups had in common was dialogue with visitors. Rather than one-way delivery of information and feelings, they asked questions and invited opinions―fostering active, two-way communication. One woman told the children at the end of her tour, "I'm truly glad I could hear what happened in Hiroshima in your own words. Thank you."

Sasaki, who also volunteers as a guide in the Peace Memorial Park, put it this way: "Peace isn't just about living without war and in safety. It also means being able to live happily and with joy. That's what I realized while guiding many people."

Not one-way, but two-way. Respecting others and recognizing diversity as a strength, they are "weaving" peace―sending forth, themselves, "one voice, one action" for the next generation.

● Children's Peace Summit(※1)

The spiritual successor to the Children's Peace Assembly of 1995, which invited children from around the world to Hiroshima, the Children's Peace Summit has been held annually every year since. As part of the City of Hiroshima's peace education, it both preserves atomic bomb experiences and fosters proactive attitudes toward lasting world peace. After essay screening, 20 sixth graders are selected to revisit the Peace Memorial Museum and exchange views at a Commitment to Peace review meeting. All twenty attend the Peace Memorial Ceremony on August 6. In fiscal 2025, to sustain momentum, participants also served as volunteer guides at the Honkawa Elementary School Peace Museum, explaining the realities of the bombing and local peace-education initiatives.

https://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/education/kyouiku-suishin/1026024/1009040.html

●Honkawa Elementary School Peace Museum(※2)

Situated just 410 meters from the hypocenter, this museum stands on the grounds of Honkawa Elementary School, where about 400 pupils and 10 staff members lost their lives. Preserving part of the heavily damaged former school building and its basement, it opened to the public in 1988 as a place where children and visitors can learn the value of peace. Hours: 9:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m. (last entry 4:40 p.m.). Admission: free. Closed: Saturdays, Sundays, national holidays, and substitute school holidays.

https://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/atomicbomb-peace/fukko/1021101/1026920/1026921/1020868.html

https://peace-tourism.com/en/story/entry-131.html

●Full Text of the 2025 Commitment to Peace

https://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/_res/projects/default_project/_page_/001/028/354/070806.pdf

Shun Sasaki

A student at Hiroshima City Gion Elementary School. About twice a month, he visits the Peace Memorial Park to volunteer as a guide, mainly for overseas visitors, using handmade materials he created with his mother. Since he began at age seven, he has guided more than 1,500 people. "We can't change the past, but we can learn from it and use it to shape the future. I want to keep guiding as much as I can." His dream is to become a doctor.

Chieri Sekiguchi

A student at Hiroshima City Minami Elementary School. She became friends with two sisters from Ukraine through a clothing-donation initiative; later, they played together in Hiroshima with an American friend she met through her mother's work. "Even if we speak different languages, we're all human. The value of life doesn't change." Her dream is to become an actor.

Related Content

Dialogue through Animation: Interview with Sunao Katabuchi, Director of In This Corner of the World

Keywords

Back Issues

- 2025.12.25 Peace Actions Envisi…

- 2025.9.30 The 51st Japan Found…

- 2025.9.30 The Japan Foundation…

- 2025.9.30 Bringing the World C…

- 2025.9.30 The 51st (2024) Japa…

- 2025.9.30 Japan Foundation Pri…

- 2025.9.30 Japan Foundation Pri…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.3. 4 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.4.10 The 49th Japan Found…